Charles J. Connick

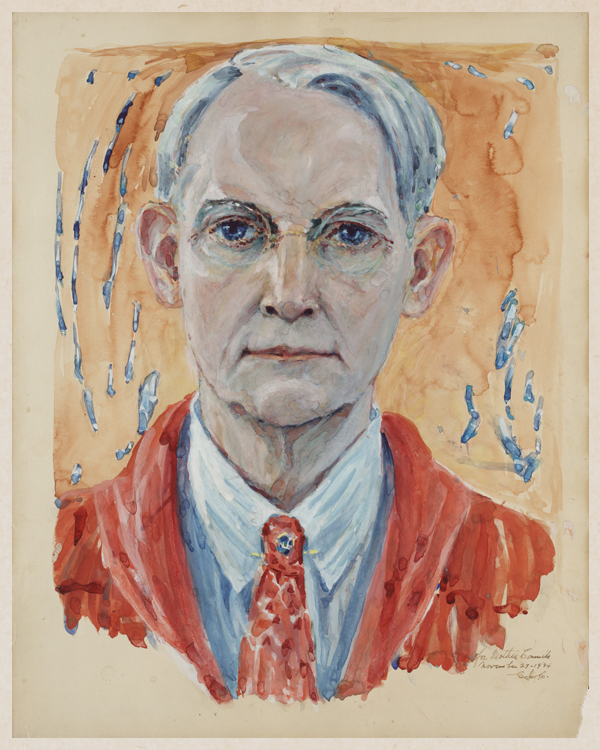

Self-portrait, 1934. Courtesy of Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Self-portrait, 1934. Courtesy of Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Artist and designer Charles J. Connick (1875-1945) was hailed as the greatest stained glass craftsman of his lifetime. Internationally renowned, he studied art in the United States and Europe and became one of the leaders of the Arts and Crafts movement in Boston, where he founded a studio which operated for 73 years.

Thousands of stained glass windows from Charles J. Connick and Associates adorn churches, chapels, synagogues, libraries, hospitals and schools across the United States and around the world.

Charles Connick c. 1885. Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution.

Charles Connick c. 1885. Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution.

Illustrations by Charles Connick for the Pittsburgh Press, July through September 1894.

Illustrations by Charles Connick for the Pittsburgh Press, July through September 1894.

Early Life

Charles Jay Connick was born in Springboro, Pennsylvania to Armina (Mina) and George Connick. Of the eleven children in the Connick family, only four survived beyond the age of twenty. A telegraph operator in his youth, George Connick moved his family to Pittsburgh in 1882, settling in the city's East End. George Connick became the manager of the Mercantile Protective Bureau. Although he was well-regarded in the business community, his business failed in 1894, leaving him heavily in debt.

The family's financial struggles put a harsh strain on Mina Connick and her children. Having grown up a poorly educated farm girl, Mina Connick could nevertheless sew and draw, and it was with these skills that she provided for her family. A diminutive woman at four feet, nine inches, she was a towering figure to her son Charles, known to all as Charlie. Cooking, mending, saving, and gardening, she maintained a spirit of joy, and the red poppies in her garden were, for Charlie, his first “spiritual message of pure color,” an example of the profound impact color could have on the human spirit. Connick would later incorporate these lessons into his stained glass designs.

Connick began drawing as a boy. A promising talent, he won prizes in student art competitions. But when his family's financial situation became perilous, Connick dropped out of high school just months after starting ninth grade. He put his artistic talent to work, earning money to help his parents and siblings by illustrating advertisements. He never finished his formal schooling.

At age 18, he was hired by the Pittsburgh Press as an apprentice illustrator. He covered sporting events and drew quick sketches of athletes and sports fans for Sunday editions of the paper.

After one such event in 1894, Connick was befriended by stained glass artist J. Horace Rudy, who was always on the lookout for artistic talent. That encounter changed the course of Connick’s life.

Light and Color

Rudy engaged Connick as an apprentice at Rudy Brothers, a start-up studio in East Liberty that J. Horace, as artistic director, ran with his brothers, Frank, Jesse and Isaiah. The brothers had come to Pittsburgh to produce stained glass windows for Henry J. Heinz.

To Connick, the studio was a “fairyland” with its frosty light piercing the jeweled tones of the many bits of glass, sending colors dancing through the air and along work benches and walls. The young artist had found his calling.

Connick served a three-year apprenticeship at Rudy Brothers until 1897 when, with J. Horace Rudy’s blessing, he gained additional experience working with other stained glass firms in the city.

In 1900, Connick moved to Boston and was hired by Spence, Moakler and Bell as a designer. He returned to Pittsburgh in 1903 and began working at Conroy, Prugh & Company. A year or so later, he returned to Rudy Brothers as manager of their Pittsburgh shop. The company had just expanded with a shop in York, Pennsylvania, and J. Horace Rudy departed Pittsburgh to head the new location.

Apprenticing under Connick at Rudy Brothers during this period was a young sketch artist named Lawrence B. Saint, who’d been discovered by J. Horace Rudy working in a wallpaper store and who would go on to head the stained glass studio for Washington National Cathedral.

In 1907, Connick was on the move again, this time to New York City and a job with Tiffany Studios. While his time in New York was brief, it was influential. For it was there that he worked with muralist and leaded-glass window maker Otto Heinigke, who had been to Europe and studied the stained glass windows of the great cathedrals. Heinigke was experienced in the traditional medieval pot-metal method of making stained glass, a very different approach than that favored by Louis Tiffany, who was developing new methods and materials such as Favrile glass.

That era was, as Connick later recalled in his 1937 book Adventures in Light and Color, “the heyday of art-glass windows.” The popularity of opalescent art glass and the amount of money Americans were spending on installing it in private residences and public buildings led to predictable results -- slick salesmanship, assembly-line production and sentimental imagery. Connick called it "art glass as big business."

The traditional approach, with its emphasis on craftsmanship, by contrast, retained the transparent "glassiness of glass," the interplay of light and deep, rich colors, and the role of stained glass windows as part of architectural design. Committing himself to mastering traditional medieval methods of creating stained glass, Connick traveled to Europe for five months in 1910. There, like Otto Heinigke, he studied and sketched the windows of the great cathedrals. He read rare books on the process and visited shops where the old art was still practiced.

J. Horace Rudy (1870-1940). Courtesy of Senator John Heinz History Center.

J. Horace Rudy (1870-1940). Courtesy of Senator John Heinz History Center.

Rudy Brothers architectural drawing for a window at DuBois High School, 1910. Courtesy of Senator John Heinz History Center.

Charles J. Connick and Associates

When Connick returned to the United States, he worked as a designer for several window glass firms in Boston. In 1913, he opened his own studio, Charles J. Connick and Associates, at 9 Harcourt Street in Boston.

In Connick's own words, his goal was to "rescue the stained glass craft from the abysmal depths of opalescent picture windows." Connick was convinced that "the color in light of a great stained glass window vibrates with a vitality like nothing else in visual art." Beauty, he insisted, could preach better than words. In particular, Connick favored the use of blue in his windows. He felt that color was most conducive to contemplation and a spirit of reverence in religious settings.

His visit to Chartres Cathedral in France had demonstrated that the medieval methods of producing stained glass had not been surpassed, and so it was on this model that he founded his studio, using both production methods and apprenticeship arrangements reminiscent of the Middle Ages. Connick was one of the leaders of the Gothic Revival movement in the United States.

In his studio on Harcourt Street, artists learned every step of the process from masters of the form, then became teachers themselves. The studio was not just a workplace; it was an arts community. Writers and musicians gathered there. Poet Robert Frost would visit and recite his verses.

This generosity of spirit was extended to the public, who were welcome to drop in and see stained glass windows being made. Laypersons could sign up for workshops to try their hand at creating medallions, small-scale works in stained glass. Connick exhibited his commissions when they were complete, before they were sent off to their ultimate destinations for installation. His mother, Mina, who lived to the age of 103, never missed an exhibition of her son's stained glass windows in his Boston studio.

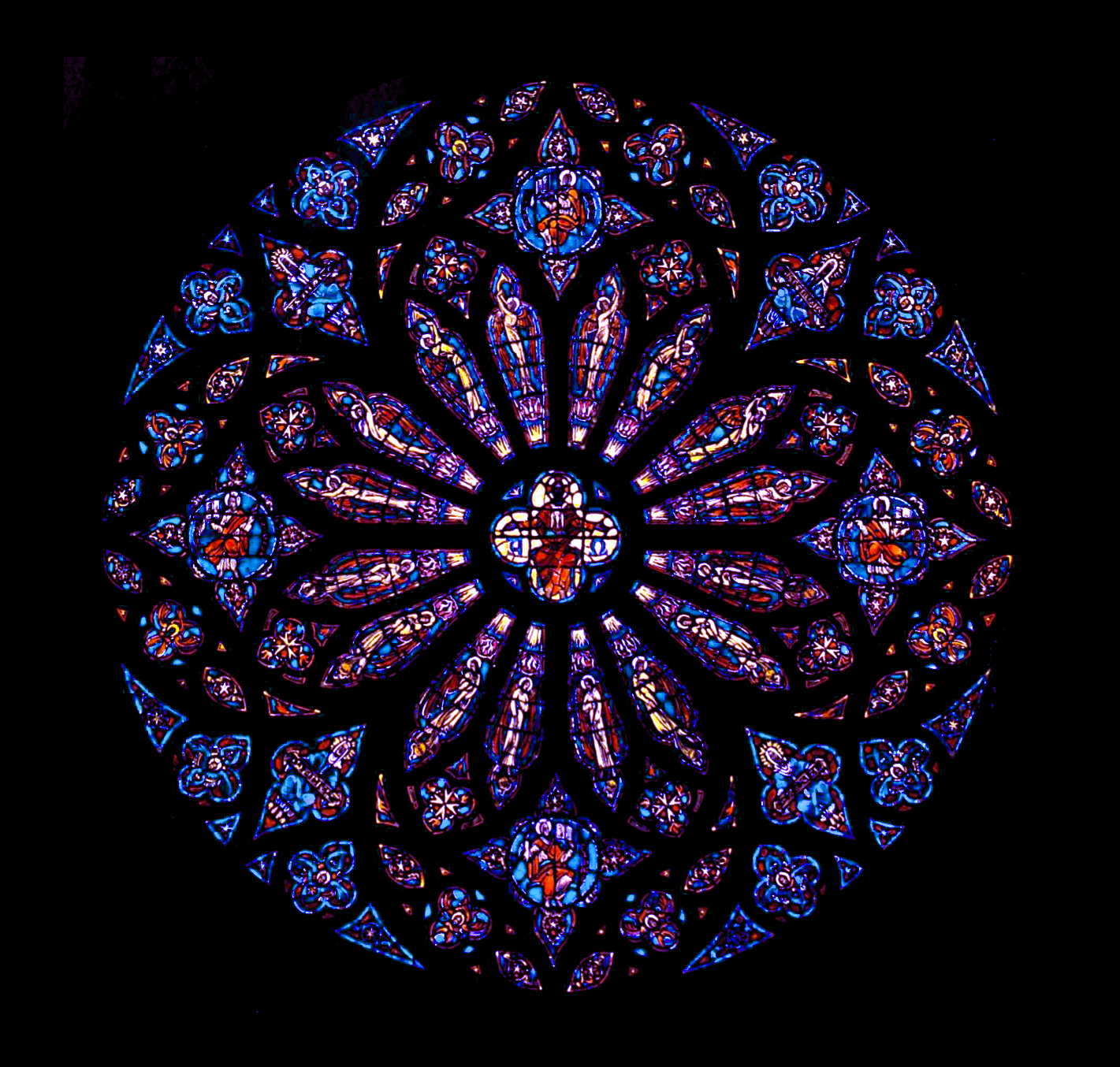

As hand-made creations by highly skilled artisans, the stained glass windows from Charles Connick and Associates were not cheap productions. The resplendent Great Rose Window for the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, made out of 10,000 pieces of glass, cost around $80,000 and was gifted by benefactor William Woodward. But Connick was an evangelist for his art as well as a businessman, and the opportunity to spread joy and beauty went beyond price. A newspaper account from 1931 related the anecdote that a young woman who worked as a domestic servant in Boston visited Connick's studio and was so taken by the majesty of the stained glass windows that she offered her entire savings to gift a window to her church. Her savings amounted to $25, and the type of window she wanted cost about a hundred times as much. Connick made the window and never mentioned the actual cost to the young woman.

Among Charles Connick's famous stained glass windows created during this period were the Great West Rose Window in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, New York City; the East Rose Window in St. Patrick's Cathedral, New York City; the "Love" and "Christian Epics" windows in the Princeton University Chapel; and windows for the American Church in Paris, Grace Cathedral in San Francisco, and the Cathedral of St. Paul in Detroit.

Always conscious of the interdependence of stained glass windows and the architecture of the buildings that hosted them, Connick was sensitive to the objectives of the architects he worked with. His collaborations with Boston architect Ralph Adams Cram were particularly fruitful. The prolific Cram, like Connick, was a proponent of Gothic Revival style.

Connick and his wife, former teacher Mabel Coombs Connick, lived in Newtonville, Massachusetts, about eight miles from Connick's Boston studio. In 1939, Connick designed a window for the Newtonville Public Library. With an appropriate literature theme, the window featured a sailing ship and an inscription from the Emily Dickinson poem, "There is no Frigate like a Book."

Charles Connick's design for the Great West Rose Window, Cathedral of St. John the Divine, New York, New York. Courtesy of Boston Public Library.

Charles Connick's design for the Great West Rose Window, Cathedral of St. John the Divine, New York, New York. Courtesy of Boston Public Library.

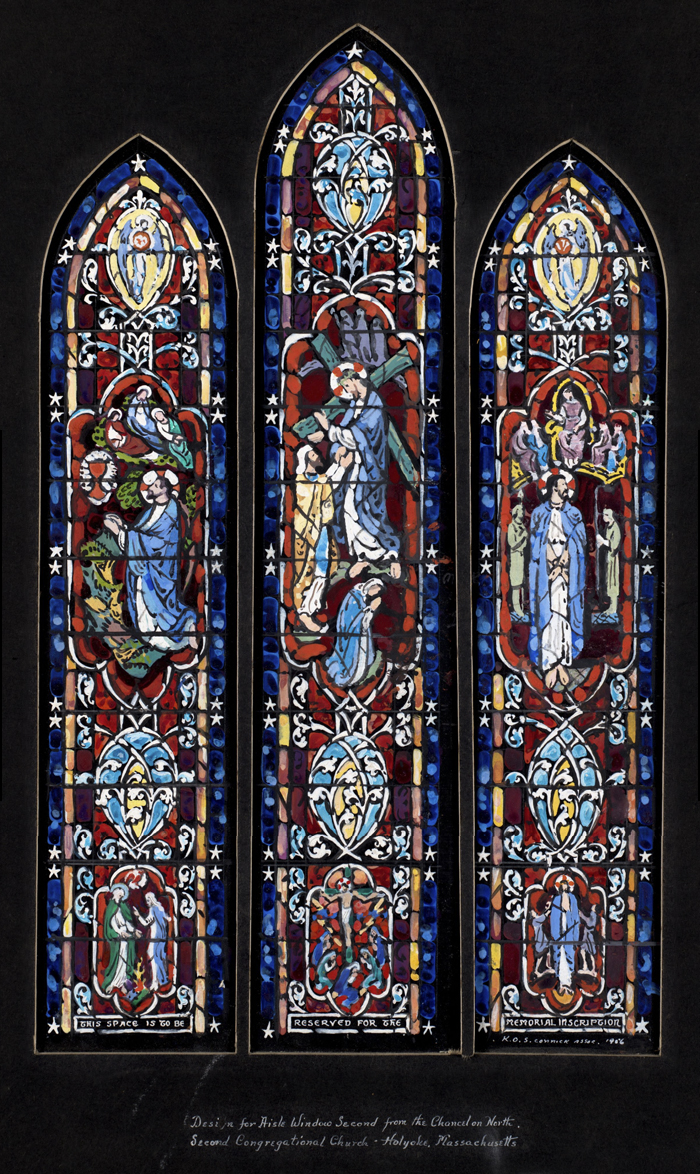

Charles Connick's design for a window in the Second Congregational Church, Holyoke, Massachusetts. Courtesy of Boston Public Library.

Charles Connick's design for a window in the Second Congregational Church, Holyoke, Massachusetts. Courtesy of Boston Public Library.

Connick Windows in Pittsburgh

Although based in Boston after 1910, Charles Connick retained close ties to Pittsburgh. He kept in touch with former associates in the Iron City and, in November 1922, appeared at the Carnegie Institute to deliver a lecture. Titled "Stained Glass as an Artist's Medium," the lecture was part of an exhibition of that art form, featuring examples of both opalescent and medieval stained glass. Lawrence B. Saint supervised the event.

Connick also created stained glass windows for houses of worship in the Pittsburgh area. Pittsburgh's First Baptist Church, Calvary Episcopal Church and East Liberty Presbyterian Church are examples of Connick's work, as is First Presbyterian Church in Greensburg.

His largest scale commission in the area was for the University of Pittsburgh, where he created stained glass for three buildings: the Cathedral of Learning, the Stephen Foster Memorial, and the Heinz Memorial Chapel.

The non-sectarian Heinz Memorial Chapel was constructed from 1933-1938. The architect was Charles Zeller Klauder of Philadelphia. Echoing the breathtaking Sainte-Chappelle in Paris, the Heinz Memorial Chapel occupies a compact footprint for a Gothic-style building but soars heavenward.

Charles Connick designed all 23 stained glass windows for Heinz Memorial Chapel. The windows were created in his Boston studio and installed in phases from November 1936 through May 1938. The lancet windows in the north and south transepts are 73 feet tall, among the tallest stained glass windows in the world. In total, 250,000 pieces of glass were used in the windows, which inspired overjoyed reactions from viewers. Ralph Adams Cram proclaimed the windows for Heinz Memorial Chapel to be Connick's best work -- faultless and "perfectly grand."

Heinz Memorial Chapel, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Courtesy of D.E. Spangler.

Heinz Memorial Chapel, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Courtesy of D.E. Spangler.

Legacy

Charles J. Connick died in Boston in December 1945. His stained glass windows outlive him. So, for several decades, did his studio in Boston, which remained open until 1986. Connick's artistic reach and influence are difficult to calculate because his connections spanned so many art forms and communities.

He traveled the world lecturing on stained glass. He was awarded medals at the Panama-Pacific International Exhibition in 1915, the Art Institute of Chicago in 1917, and the American Institute of Architects in 1925. Princeton and Boston University gave him honorary degrees. He was president of the Stained Glass Association of America from 1931-1939 and a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

He was a teacher and coworker to every person, man or woman, who created objects of beauty in his studio. These people included stained glass artists Orin E. Skinner, who was Connick's "left-handed right-hand man" at the studio, and Knute Svendsen, chief designer at Charles J. Connick and Associates from 1943-1963. Paul Child, the husband of celebrity chef Julia Child, worked as a cutter and glazer at the studio around 1930 and helped create the windows for the American Church in Paris.

Stained glass artist Rowan LeCompte, who designed more than 40 windows for Washington National Cathedral, started working with stained glass as a teenager but found material scarce to come by during World War II. It was Charles Connick who gifted imported glass to the young LeCompte which allowed him to continue to create.

During its 73 years in operation, Charles J. Connick's studio produced more than 15,000 stained glass windows as part of 5,000 commissions. For each commission, the studio kept meticulous records -- correspondence, contracts, watercolor sketches, photographs, slides, negatives and press clippings. When the studio closed, these records were donated to Boston Public Library and Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The Charles J. Connick Foundation, a non-profit organization, was created in 1985 to promote appreciation for the art of traditional stained glass making.

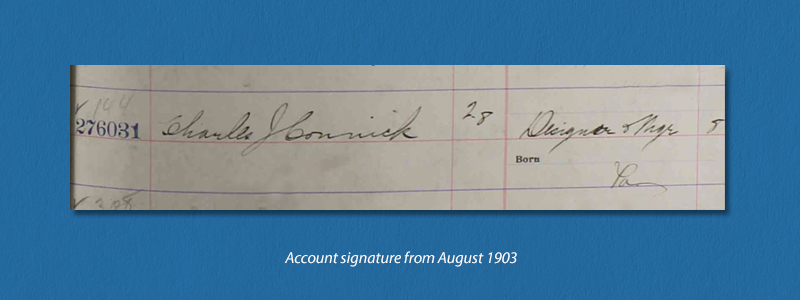

Charles J. Connick opened a savings account at Dollar Bank in August 1903.

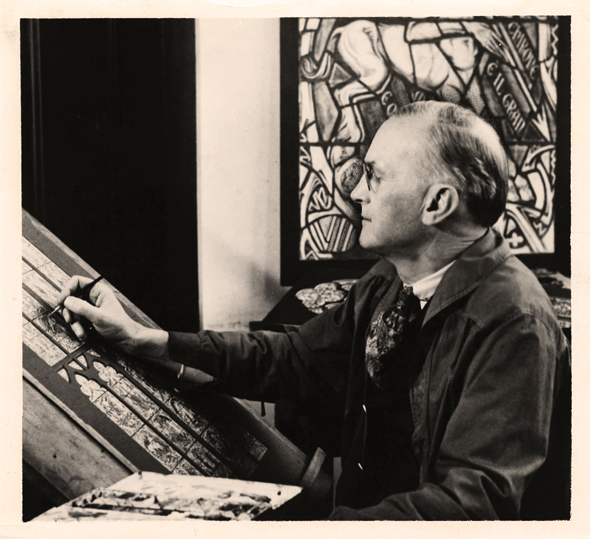

Charles Connick in his Boston studio. Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution.

Charles Connick in his Boston studio. Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution.

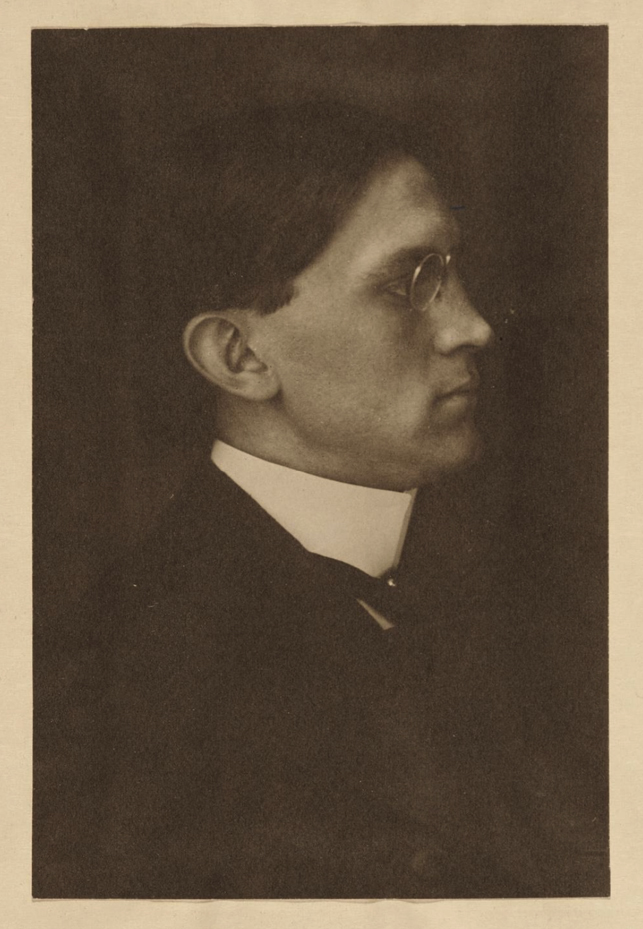

Charles J. Connick in 1902. Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution.

Charles J. Connick in 1902. Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution.